Author:Wall Street CN

Key points

Interest rates have reversed between China and Japan, with global funds now favoring China's lower interest rates. This is because, in addition to interest rates, exchange rates also influence capital flows. Japan is experiencing "bad" inflation, with rising interest rates but a depreciating currency; China is experiencing "good" inflation, with relatively low interest rates but a strong currency.

The real meaning behind the interest rate reversal in China and Japan is that the global supply chain has been and continues to be profoundly reshaped.Most countries (including Japan) are suffering from imported inflation after the continued hollowing out of their manufacturing sectors.

Caught between the two superpowers, the US and China, Japan's path to technological advancement and reindustrialization will not be easy. Like inflation, Japan's interest rates will be on the verge of collapse.

China's relatively low inflation is a result of price restructuring during the transition from old to new growth drivers. A complete industrial system, energy independence, and food security are also key factors.China is a rare country that was able to sever the chain reaction after the real estate crisis: "declining housing prices -> capital outflow -> currency depreciation -> imported inflation." Leveraging its technological and manufacturing advantages, China will eventually emerge from low inflation and enter a new cycle.

summary

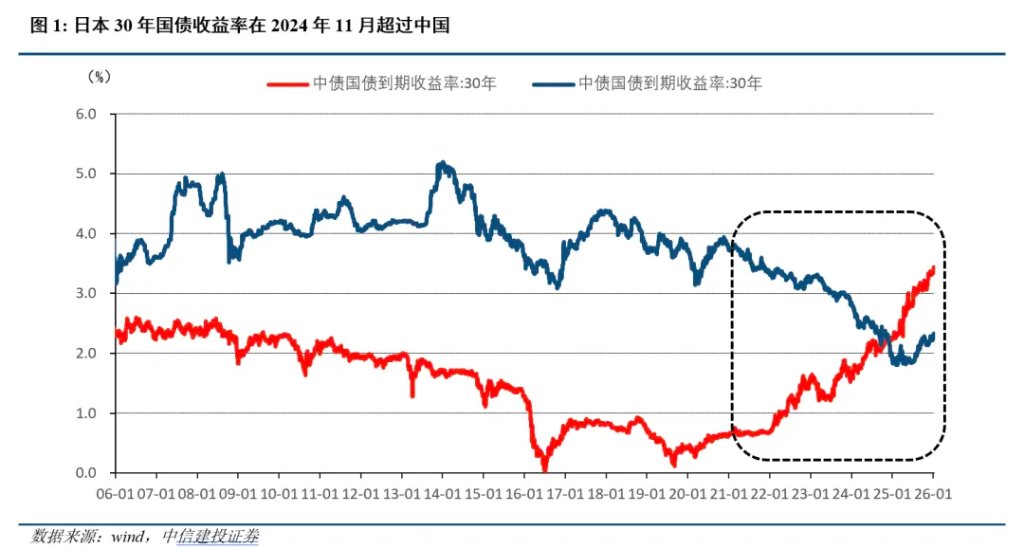

The gears of a reversal in the interest rate system of Chinese and Japanese government bonds began to turn in 2024. Intuitively, high interest rates correspond to high growth, and low interest rates to low growth; this represents a reversal of the interest rate matrix between China and Japan. According to the basic theory of interest rate parity, capital flows from low-interest-rate countries to high-interest-rate countries. Does this reversal in interest rates between China and Japan mean that capital will flow from China to Japan?

Once we clearly understand the inflation behind interest rates and find the underlying economic logic reflected by inflation, we can deeply understand the reversal of interest rates between China and Japan. In the future, we will follow the counterintuitive conclusion that funds will not flow from low-interest-rate countries to high-interest-rate countries, but rather from Japan, where interest rates cannot be suppressed, to China, which has a complete industrial system and strategic security in energy and food, even though China's interest rates are not high at present.

Why is this so counterintuitive?

Our first observation is that the reversal of the interest rate matrix between China and Japan is a historically rare phenomenon.

In 2024, the yield on 30-year Japanese government bonds officially surpassed that of China. This trend quickly spread to the short end, and in 2025, the yield on 10-year Japanese government bonds officially surpassed that of China, while the yield on 1-year government bonds also showed a trend of catching up with China.

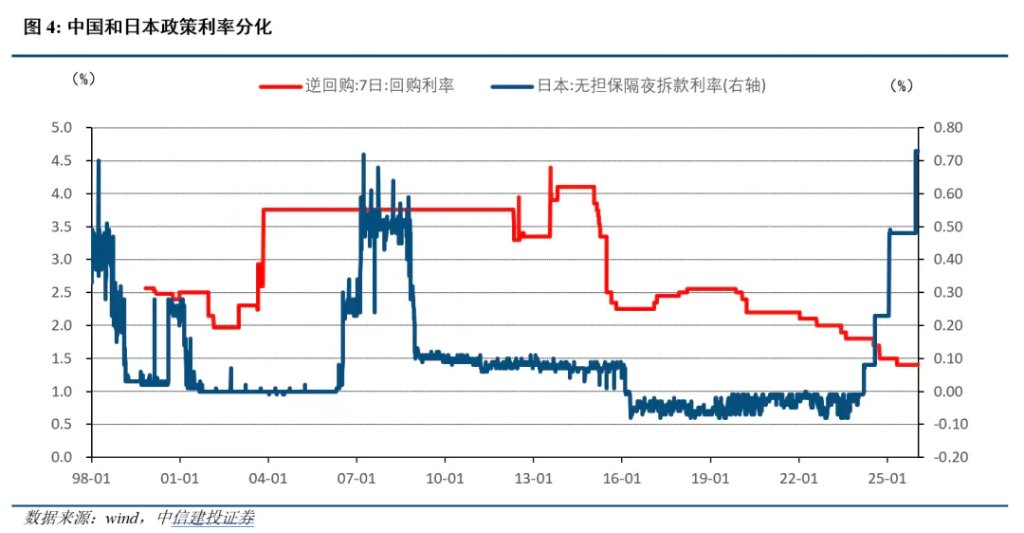

Beneath the surface of the inverted yield curve lies a dual misalignment between the monetary policy cycles and inflation cycles of the two countries.

From the perspective of monetary policy,Under the principle of "taking our own interests as the main focus," the People's Bank of China has been in an easing cycle of interest rate and reserve requirement ratio cuts in order to offset the downturn in the real estate cycle and insufficient domestic demand. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan was forced to say goodbye to its decade-long quantitative easing policy, withdraw from yield curve control and negative interest rate policies, and enter a cycle of interest rate hikes in this round of global inflation.

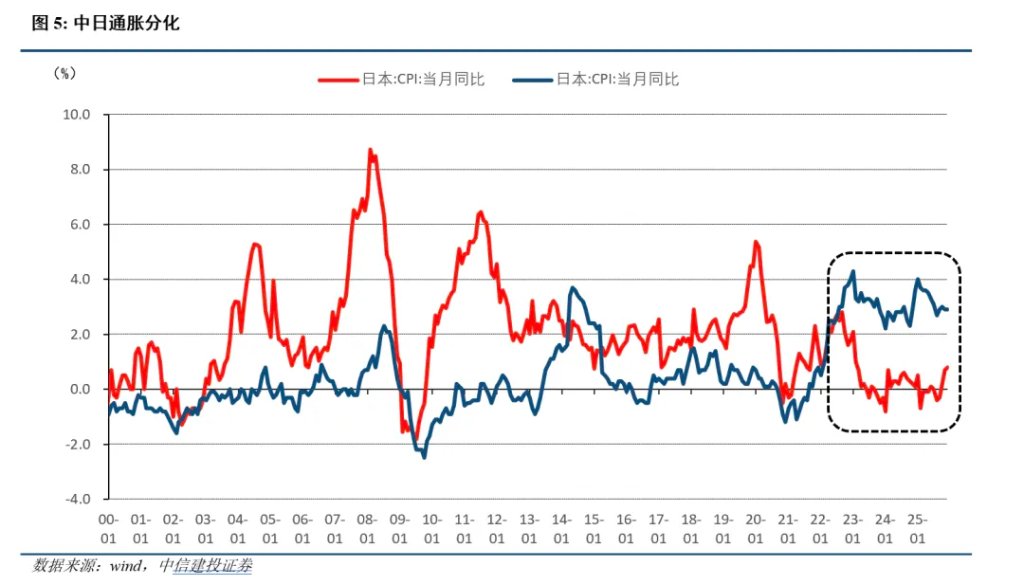

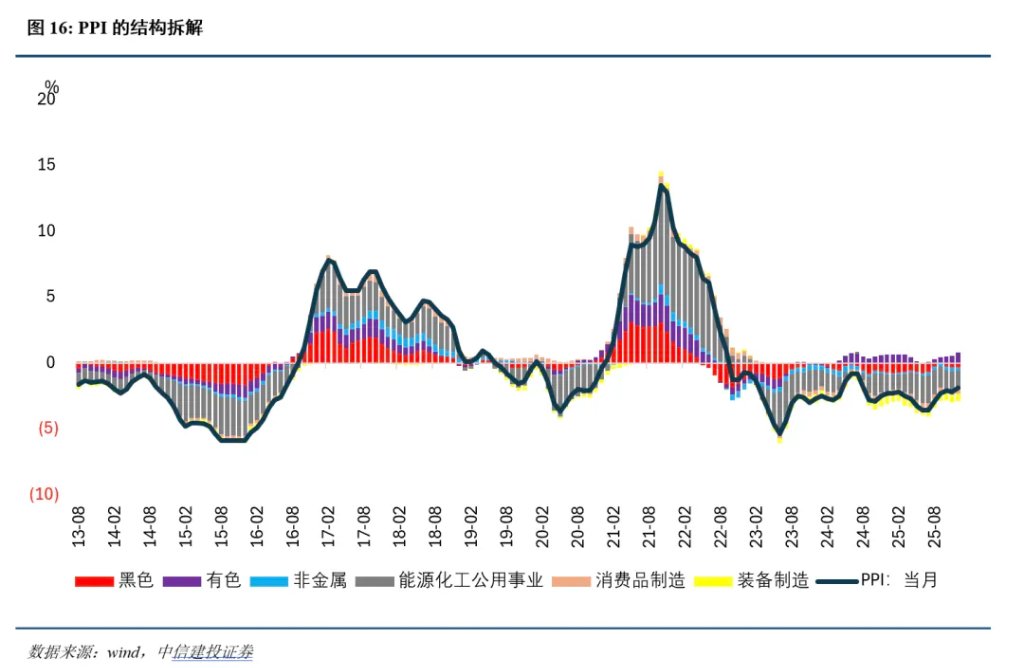

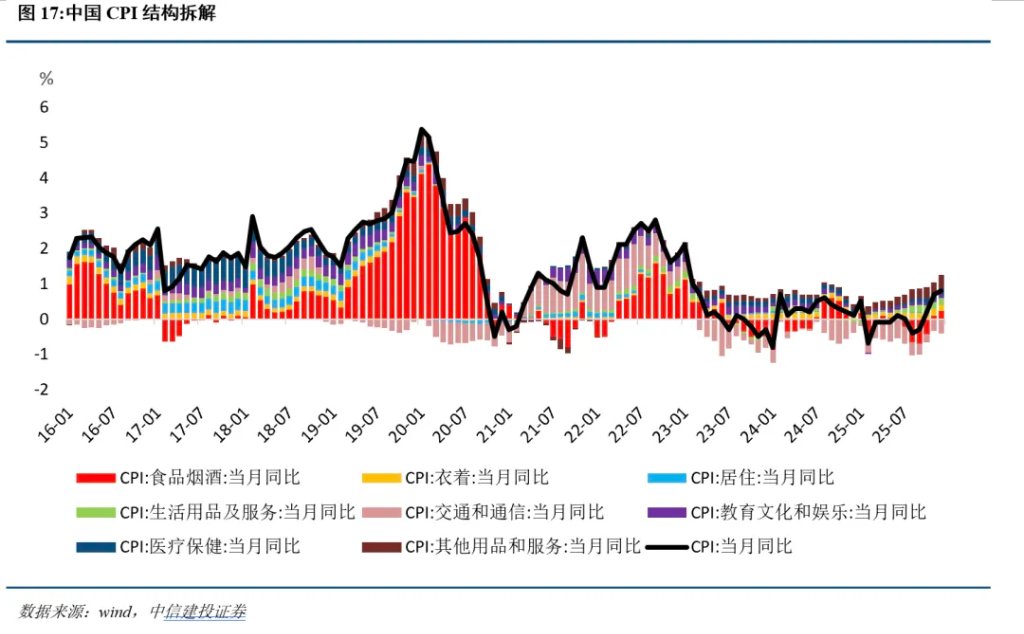

From the perspective of the nature of inflation,China's current low-interest-rate environment reflects the low levels of CPI and PPI, indicating price reshaping during the transition from old to new growth drivers; while Japan's soaring interest rates are due to its recovery from the "lost three decades," resulting in a systematic upward shift in the inflation center.

Does Japan's high interest rates and high inflation signify economic prosperity? Quite the opposite; rather, they are evidence of Japan's economic transformation towards Latin America.

The market often harbors optimistic fantasies about Japan emerging from deflation through "economic recovery," but a deeper analysis of the causes of this round of inflation in Japan reveals a dangerous "Latin Americanization" characteristic—that is, stagflation-like conditions caused by "imported inflation + supply-side constraints," rather than healthy demand-driven growth.

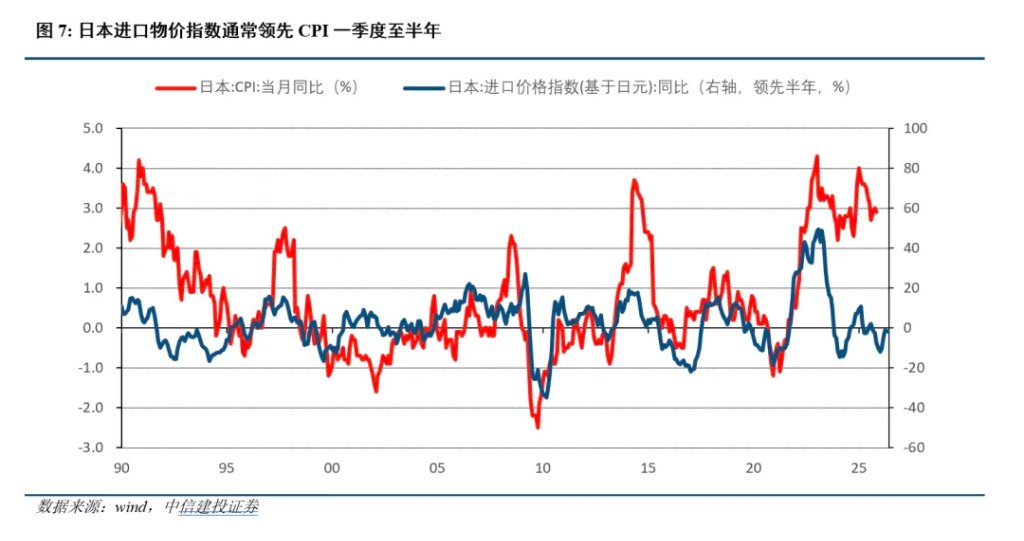

The recent reversal of inflation in Japan was mainly driven by three forces, all of which were characterized by negative supply shocks.

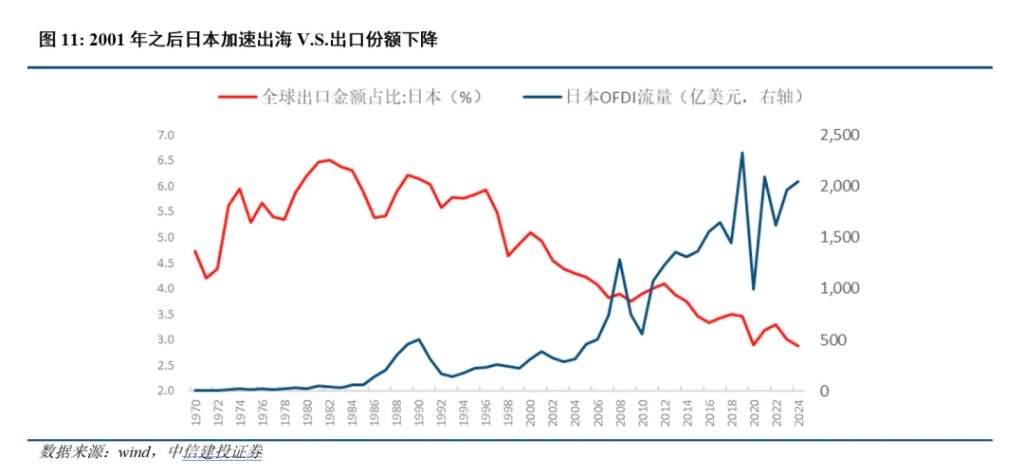

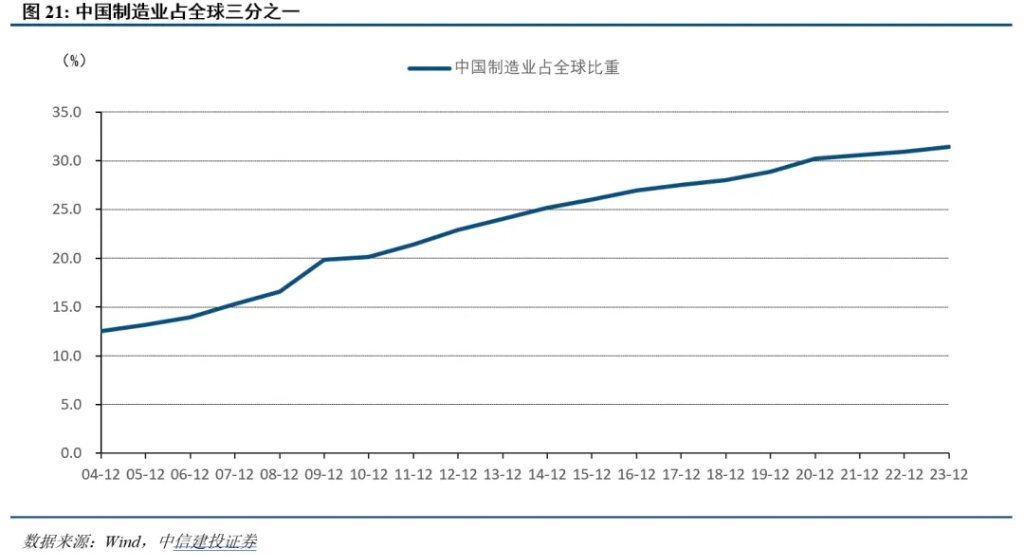

First, the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector has made Japan very sensitive to imported inflation.Since China's accession to the WTO in 2001, Japan has accelerated its "outward investment-driven nation-building" strategy, leading to a large-scale overseas expansion of its domestic manufacturing sector and leaving a significant supply gap domestically. This altered the Japanese economy's sensitivity to exchange rates: Japan transformed from a beneficiary of currency devaluation into a victim. Lacking domestic alternatives, when global commodity prices rise, Japan cannot stabilize prices by increasing domestic supply and can only rigidly bear the brunt of imported inflation. The overseas relocation of manufacturing is merely one channel for the hollowing out of Japan's manufacturing sector. The real reason for this hollowing out lies in Japan's limited scale, making it unable to maintain a complete industrial system. With the rise of China, a manufacturing powerhouse, the hollowing out of Japan's manufacturing sector is an inevitable trend.

Second, the long-term loose monetary policy has become an amplifier for imported inflation.The Bank of Japan's long-term financial repression backfired during the global interest rate hike wave of 2022. In its attempt to maintain artificially low interest rates, Japan diverged from the policies of major central banks worldwide in an unprecedented manner, leading to a collapse in the yen's exchange rate. This currency depreciation, triggered by a divergence in monetary policy, resonated with the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector, significantly amplifying the import costs of energy and raw materials. This meant that financial repression ironically became a catalyst for soaring inflation.

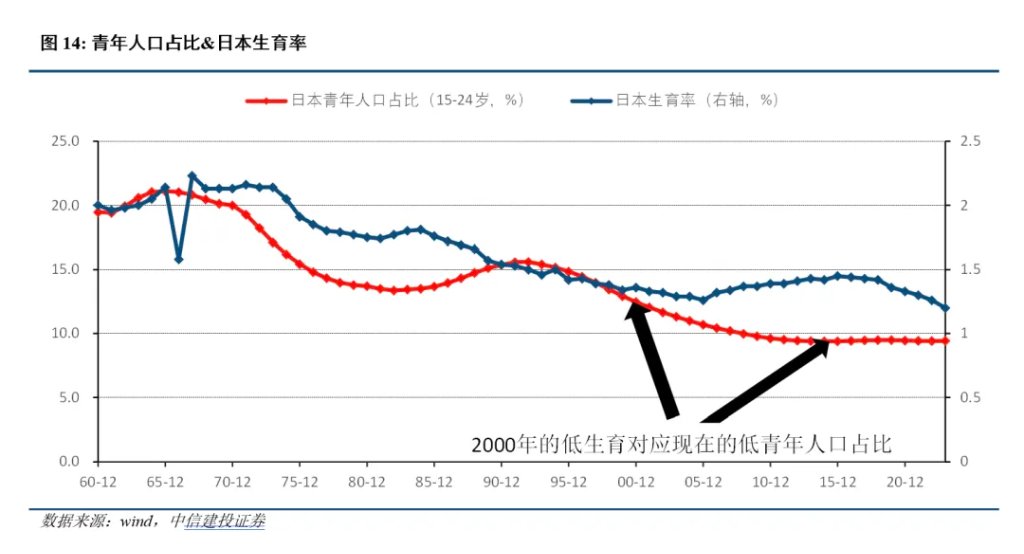

Third, population decline has led to imported inflation successfully transforming into a "wage-price spiral".If the former two factors triggered inflation, then demographic issues made it more persistent. The labor supply gap caused by aging was fully exposed after the pandemic, and the severe labor shortage in the service sector forced companies to passively raise wages significantly. This "defensive wage increase," which stemmed not from productivity growth but from supply shortages, directly resulted in wages maintaining a high growth rate of over 5% in 2024-2025, transforming external pressures into internal long-term inflationary stickiness.

In summary, Japan is experiencing a predicament similar to that of Latin American countries. Deindustrialization has led to inelastic supply, currency devaluation has directly translated into inflation, and labor shortages have locked in a price floor. This is a painful form of "bad inflation" that forces the central bank to raise interest rates against the backdrop of a weak economy.

Does China's low interest rates and low inflation indicate a deep economic recession? A more accurate understanding is that China is undergoing price restructuring under the transformation of old and new growth drivers.

In stark contrast to Japan's "bad inflation," China's current low-inflation environment should not be simply defined as "deflation."It's more like a price restructuring under the fierce clash between old and new growth drivers.

The structural divergence in inflation data accurately depicts this picture.

On the one hand, the decline of old growth drivers has brought deflationary pressures to the demand side.With the end of the "golden age" of real estate, the real estate chain is facing deep destocking. The negative wealth effect caused by the decline in housing prices has suppressed residents' willingness to make discretionary consumption, which is the core drag on the current weak CPI and PPI.

On the other hand, the rise of new growth drivers has led to "technical price reductions" on the supply side.In sectors such as non-ferrous metals, power equipment, and new energy vehicles, the price decline is not due to a collapse in demand, but rather to the strong cost reduction and efficiency improvement capabilities of China's manufacturing industry. Chinese companies have driven down the prices of high-tech products such as electric vehicles and consumer electronics through extreme supply chain efficiency.

Therefore, China's low inflation is a complex product: it is a result of both the painful clearing caused by the deflating of the real estate bubble and the benign cost reduction brought about by industrial upgrading.

This is a price manifestation of "creative destruction," not the inevitable fate of a prolonged recession. As new productive forces gradually outnumber old drivers in the economy, this structurally low inflation will translate into higher-quality growth.

Let's further understand the profound implications of the interest rate reversal between China and Japan.

Low inflation and low interest rates reflect the temporary limitations encountered in China's economic development, but at a deeper level, they also reflect the supply advantages of the Chinese economy.

Looking back at global economic history, the bursting of real estate bubbles often serves as the prelude to malignant stagflation, rather than a smooth path to low inflation. China's ability to maintain price stability during a period of deep real estate market adjustment is precisely evidence of the advantages of a major power with a complete industrial system and monetary sovereignty.

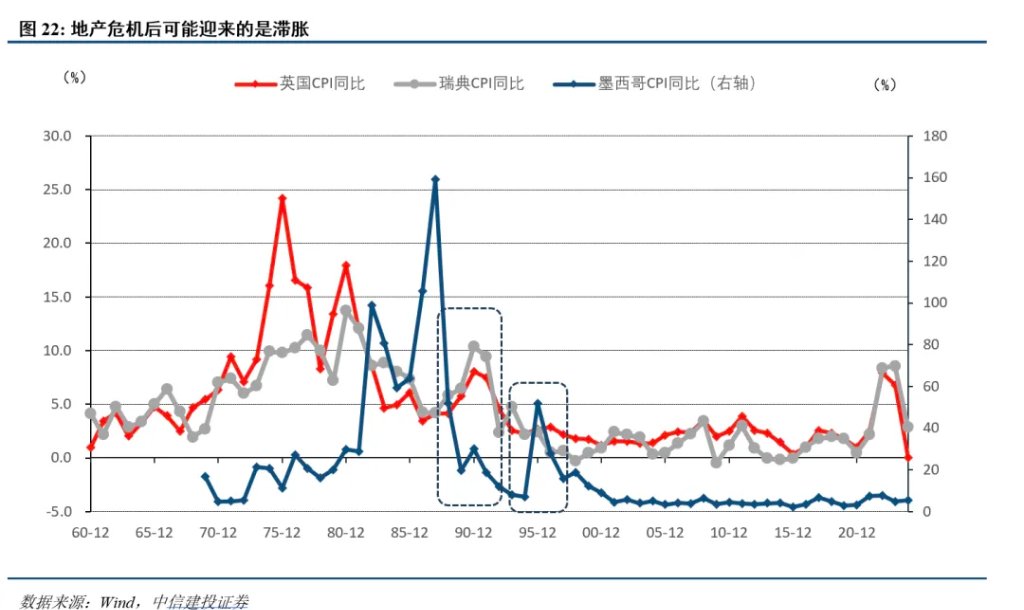

The lessons of history are painful.Mexico, the UK, and Sweden in the 1990s all suffered currency collapses after their real estate bubbles burst. Due to weak domestic manufacturing bases or high dependence on foreign trade, capital flight triggered currency depreciation, leading to uncontrolled import prices and stagflation characterized by "collapsed asset prices and soaring cost of living."

China's exception stems from its strong supply-side capabilities.

The first is the completeness of the industrial chain.As the only country in the world with a complete range of industrial sectors, China is a producer of goods rather than simply a consumer. Its strong domestic manufacturing capabilities ensure that even during exchange rate fluctuations, the vast majority of industrial and consumer goods in China maintain ample supply and stable prices, forming the first line of defense against inflation.

The second is the security barriers to energy and food.Although China relies on imported crude oil, its energy is mainly based on coal, and it is vigorously developing new energy alternatives. In terms of food, the high degree of self-sufficiency in staple grains means that fluctuations in international grain prices cannot directly impact domestic prices.

Let's look at the upward trend in Japan's post-pandemic inflation center.

Japan's post-pandemic inflation was not a welcome phenomenon, but rather a consequence of its long-term hollowing out of its manufacturing sector, which struggled to absorb imported inflation. The nature of Japan's inflation can be seen in the depreciation of the yen.

Because the underlying logic of inflation differs between China and Japan, the flow of capital under the misalignment of inflation and interest rates does not entirely follow intuitive assumptions. Capital doesn't flow from low-interest-rate China to high-interest-rate Japan, with the exchange rate being the most critical variable hindering this flow. Conversely, Japan's inflation, exchange rate, and interest rates all indicate a stagflation, while the situation in China is quite different. China's relatively low interest rates reveal a strong supply advantage. Consequently, capital flows from Japan to China.

text

source:

No Comments